LIGHTWEIGHT TRAINING EQUIPMENTNew lightweight barbells and bumper plates signal a new era in sports training for women athletesBy Laura Dayton Published: Fall 1998 Like the Nehru collars and striped stovepipe polyester pants of the 60s, there are some things us old folks remember but just don't like to talk about. For coaches, a period they'd like to forget is when weight training was frowned upon. Hard as it might be to believe today, there was a time in our not too distant past when coaches believed weight training made athletes slower, ruined their endurance, wreaked havoc with their coordination and made the poor souls so muscle-bound that they couldn't comb their hair. We laugh at such nonsense now, because we know better. However, there is one aspect of weight training that is still shrouded in the same type of antiquated and often ignorant thinking. That area concerns women and weight training, and in that regard, it's often still a man's world. Many male coaches simply don't really know what to do with women. Do you train them like bodybuilders, but assure them that they can't build big muscles—despite what those freaky women physique stars look like on late-night ESPN? Do you tell them to perform ultra-high reps for toning? Do you make sure they do lots of aerobics so they won't, as one famous European weightlifting coach once remarked, "acquire the body of a man"? Or, do you do what BFS President Dr. Greg Shepard does, which is teach them how to become better, faster and stronger? A Better Way to Train The biggest problem for women is that weight training by traditional bodybuilding methods (i.e., two-to-three exercises for three sets by 10 reps for each body part), may produce a masculine-looking physique. Sure, without the aid of steroids women will always be smaller versions of their male counterparts, but bodybuilding can impart some undesirable attributes in women athletes. However, bodybuilding training is not the most effective way to develop female athletes, or male athletes for that matter. Explosive weight training movements, such as the power snatch and the power clean (a BFS core lift), are what will give today's female athletes the edge. Further, these lifts will not develop Arnold Schwarzenegger-type physiques! However, Olympic lifting for women has been a hard pill for many coaches to swallow. Strangely enough, the very sport that had the most difficult time accepting the fact that women should perform Olympic lifting was Olympic lifting itself. Through a slow but progressive evolution of opinions and rules, women will, for the first time, be eligible for medal competition in the upcoming Olympic Games. This is a significant milestone, considering that women have been participating in Olympic lifting events for several decades, but have never been medal-eligible and for years were hampered by a set of rules that discriminated against them. It took many years for the Olympic lifting federations to recognize that women needed a separate set of rules. Like male coaches who are bewildered over how to train their female athletes, the decision-makers in weightlifting dealt with the problem by having women follow the same rules as the men. This decision didn't do women any favors. The Evolution of Acceptance In weightlifting, each athlete is given three attempts in each of the two lifts, the snatch and the clean and jerk. The first hurdle that women faced was the rule that they must increase their weights by five kilos (11 pounds) between their first and second attempts. That may not seem like much, but it can be a major ordeal for the average female. To keep the math simple, we'll use a 99-pound female who is trying to snatch her bodyweight (something that even our super-heavyweight Mark Henry didn't accomplish in the 1996 Atlanta Olympics). Our female lifter would most likely start with 83 pounds (37.5 kilos) for her first attempt, for the simple reason that anything less would be ludicrous. For her second attempt she would have to jump to at least 94 pounds (42.5 kilos), then finish with 99 pounds (45 kilos). Coaches who are used to athletes who weigh closer to 200 pounds than 100 pounds may see nothing wrong with such a progression. However, if the same increases were imposed proportionately on a male trying to snatch 300 pounds, he would have to start with 255 pounds followed by 285, a jump that would be regarded as excessive when you consider the technical differences between lifting the two weights. Then for his final attempt, he would jump 15 pounds to reach 300, a jump that in a tight competition many coaches would consider excessive. To their credit, the international weightlifting powers eventually recognized this problem and allowed 2.5-kilo (5.5-pound) jumps between the first and second attempts. These small increments made it easier for beginning-level women to compete, and also made for more interesting competitive strategies for both men and women lifters. Also to the sport's credit, after a brief period in which a record had to be broken by 2.5 kilos (5.5 pounds), it went back to allowing world records to be broken by .5 kilos (1.1 pounds) to enhance the sport's progression. As an analogy, can you imagine how the 100-meter sprint (or for that matter any running event in track and field) would be affected if all world records had to be broken only in increments of five seconds? Another rule was eventually changed concerned weightlifting apparel. In the early days, women had to wear the same lifting suits as men—I suppose this is a great look if you want to become a pro wrestler or join the circus. This may not sound like such a big deal, but I doubt if Pete Sampras would appreciate it if he were forced to wear a tennis dress! In protest, several of the European women at one of the first World Championships gave themselves "wedgies" and tied knots in the suits to make them more flattering. Injury-Proofing the Female Athlete In recent years many individuals have tried to instill a fear in athletes and coaches that Olympic lifting was dangerous—and heaven forbid that a woman compete in the sport! The appropriate way to train, according to some, was very slowly. As for exercise selection, they insisted the emphasis should be on nonspecific bodybuilding movements, and the less emphasis on freeweight lifts the better. Responding to such propaganda is exercise scientist Dr. Mel Siff, who did his Ph.D. thesis on the biomechanics of soft tissues. According to Siff, the basic activities that occur in most sports, such as running and jumping, "can impose far higher forces on the body than are encountered in weightlifting." Thus, if you tell athletes they can't do lifts such as the power clean because of ballistic loading, then you should likewise tell them not to play sports, period. And if you tell athletes never to lift weights overhead as in a push press or jerk, then you should not allow them to throw footballs or baseballs either. Siff also emphasizes that the danger of weightlifting prematurely closing the growth plates of young girls is exaggerated, since running and jumping can impose even greater loads on the bones and joints. If we were to take this myth seriously, then we would have to restrict all girls and boys to walking and swimming! Another factor not considered by the slow-training proponents is that Olympic lifting can help prevent injuries by properly developing the nervous system. Siff says these same people make the mistake of concentrating on how much weight is being lifted. "The most important thing in regard to injury-proofing the athlete is proper development of the central nervous and motor control systems. From my research and experience, I have found that accidents and injuries often have a lot to do with motor control, technique and skill, and not so much with weak tissues." Siff adds that an understanding of the importance of the central nervous system explains why boxers can take so many hits, hits that would generally knock out even a well-muscled individual. "Boxers kno |

|

|

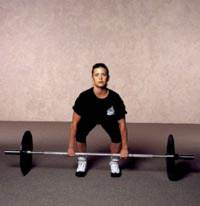

Shown above, Christy works with an Ultra-Lite Bar and 10 lb Bumper Plates. These training essentials make it easy for any women to begin training. |

|

|

This entire set up weighs only 50 lbs. (30 lb. Ultra-Lite bar and 10 lb Bumpers). Using the Aluma-Lite bar and BFS Training Plates (see page 52) make the weight only 25 lbs.! |

|

|

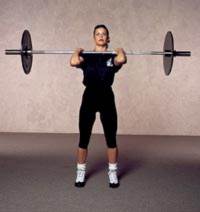

Learning the Power Clean is easy with BFS Training Plates and Aluma-Lite Bars. |

|

|

The BFS Training Plates and Aluma-Lite Bar makes it easy for anyone to learn the quick lifts. |

|

|

The Aluma-Lite Bar only weighs 15 pounds and the plates weigh only 5 pounds each. That makes a total of only 25 pounds! |

|

|

The Ultra-Lite Bar provides an excellent way to move up. With a weight of 30 lbs. it’s 15 lb less than a typical Olympic Bar. Shown here with BFS 10 lb. Bumper Plates, another training essential from BFS. |