"WORLD'S GREATEST ATHLETE"Gold medal decathlete Dan O’Brien has repeatedly defied the odds to come out on top and wear proudly the title “World’s Greatest Athlete”By Laura Dayton Published: Spring 1998 Points. Totals. Stats. Numbers are what count in sports, especially in the decathlon. But on the day Dan O’Brien was born, the stats on this future world record decathlete didn’t look so promising. Matter of fact, they were pretty bleak. Dan was born in 1966 to a Finnish mother and African American father. He was abandoned at birth and left to spend the first two years of his life in foster homes. Dan was luckier than most when Jim and Virginia O’Brien fell in love at their first sight of this spindly-legged little toddler who couldn’t sit still. Dan was taken into the O’Brien’s Klamath Falls, Oregon, home and given their Irish name. Eventually the O’Brien clan would include eight children, six of them adopted and of Asian, Native American and Hispanic origins. This eclectic group was seen often trading up seats at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics to get closer to their brother and his gold medal performance. Always at the forefront of the group were Dan’s parents, Jim and Virginia, and the Olympic cameras didn’t miss the constant acknowledgments exchanged between the O’Briens in the bleachers and the O’Brien on center stage. Despite this loving and supportive family, Dan had been a troubled student. Hyperactive and unable to concentrate, he was disruptive in class. In order to vent his pent-up energy Dan would run—to and from school, across the fields and later around the Little League bases. His mother recalls how people would come to the baseball games just to watch Dan run. Not surprisingly, Dan was eventually diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder. Knowing the cause of his hyperactivity helped, and although the condition became fully manageable, academics were still an uphill climb. Young Dan would labor through the first part of his school day, his spirits kept high only by the prospect of getting to PE. There, on the track, Dan was an athletic genius and a coach’s dream. Dan’s natural athletic talents earned him star status in high school track, baseball and basketball. He laments that for him, sports were easy, too easy. “I never had to work at any sport,” says Dan, now 31 years old. “I didn’t appreciate what I had and I hadn’t learned the difference between being athletic and being an athlete. I hadn’t learned the discipline or dedication.” Dan was recruited by the University of Idaho and soon found that a good-looking jock gets plenty of invitations to parties. “I don’t think I’m an exception considering the circumstances,” says Dan about his early college days. “I partied, I stayed up all night, I drank a lot of beer. It was the first time I’d really been away from home and the temptations were there. I was doing what most of the kids were doing, and I was having a blast. It’s just that as an athlete, I learned I can’t be like most of the other kids.” The lesson didn’t come easy. First, Dan had to lose his scholarship. He had to phone home and tell his parents. He had to take stock of his lifestyle and make some changes. He did, and the next year he started over again, enrolling in a junior college and for the first time, training with a new seriousness and discipline. In 1988 Dan made a decision that would change his life; he decided he wanted to be a decathlete. “Milt Campbell was one of my mentors,” says Dan about the former decathlon gold medalist. “There is so much history in the sport; so much dedication and pride in it. I love the story about Jim Thorpe, how after he won the first decathlon, the king of Sweden shook his hand and said, ‘Sir, you are the world’s greatest athlete.’ When I heard that story I knew that what I wanted to be wasn’t just a great athlete, but the world’s greatest athlete.” In 1991 Dan’s goal came within reach when he became the Decathlon World Champion. The No-Heighter With the 1992 Olympics looming, Reebok saw tremendous marketing potential in two of the U.S.’s top contenders for the decathlon: Dave Johnson and Dan O’Brien. The “Dan or Dave” ad campaign was launched on Super Bowl Sunday, and overnight the pair became celebrities. Who would win in the showdown at Barcelona—Dan or Dave?—was the question the advertising campaign centered upon. The only problem was Dan never made it on the Olympic team for Barcelona. “I will never know exactly what went wrong that day,” says Dan in quiet resignation, shaking his head and obviously waiting for the interview to move ahead. “I just don’t know.” What happened was Dan missed all three pole vault attempts at the Olympic trials. His “no-heighter” cost him his place on the U.S. team. Thanks to the publicity machine at Reebok, Dan’s no-heighter was the most publicized athletic failure of the year, or perhaps decade. For Dan, the public humiliation was tremendous. Sportswriters said he lacked the heart and guts of a true competitor, and that he was a much ballyhooed athlete with no discipline. Reebok dropped him like a hot potato. In a few minutes, Dan went from feeling on top of the world to the depths of depression. But while the media questioned Dan’s true talent and potential, Dan knew that the no-heighter was a fluke. He had never done it before, and now he was determined that he would never do it again. “I can’t explain what happened that day, but I realized I would have to be totally prepared for any eventuality in the future,” says Dan. “It took a few weeks, and quite a few calls from friends, family, coaches and other athletes. Then I was back into training and totally focused.” Dan’s effort paid off almost immediately. Although he didn’t compete at Barcelona, a few months later Dan entered the decathlon event in Talence, France. There he set a new world record—8,891 points—a record that still stands today. For Dan, he had proven to himself that he had what it takes to be the world’s greatest athlete. But the public only remembered the no-heighter. To truly redeem himself, and earn the title he so fervently desired, Dan knew he needed the Olympic gold. Dan went on to win two more world championships before the 1996 Olympic trials came around. Once again, all eyes were on Dan, and the event they watched most closely was the pole vault. “I knew it was a big deal,” says Dan. “But I wasn’t worried in the least. It was no longer an issue for me. I wasn’t even worried about the trials. I had one goal; that was the gold. Not the bronze, not the silver. I knew exactly what I wanted and was counting the days to Atlanta.” He sailed through the trials. In Atlanta, he sailed through the decathlon, holding on to a steady point margin throughout each of the ten events. Dan became the first American to win the decathlon since Bruce Jenner in 1976. His only disappointment was that he did not break his own world record. That is a goal he is still working on. Historic Parallels For those who follow the sport of decathlon, the parallels between Dan’s life and that of the first gold medal decathlete, Jim Thorpe, cannot be ignored. Both were born of mixed races. Both have Irish surnames. Both came from small schools and towns. They have each enjoyed immense popularity and adulation, and also humiliation. For Thorpe, stripped of his medals after a controversial decision by the governing Olympic board, redemption and restoration of those medals would occur only after his death. Dan O’Brien was able to set the record straight and place his own name for all time on the list of the World’s Greatest Athletes. But his story is far from finished. Dan feels strongly that his story is one that can help inspire and fuel other young athletes. “I don’t try to hide from the fact that I’ve made mistakes; we’re all only human,” says Dan. “There were a lot of things in my life that could have pulled me down. I had excuses to fail but I didn’t let them take hold of my psyche. I knew I was a winn |

|

|

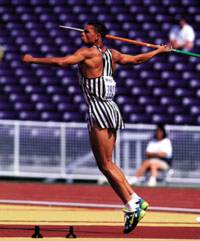

Dan Throwing the Javelin |

|

|

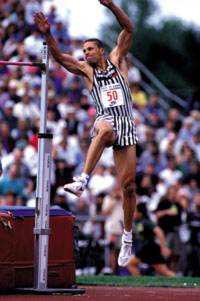

Dan high jumping |

|

|

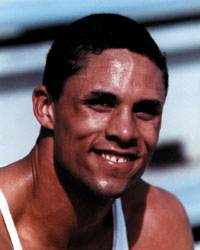

Dan O'Brien |